Mission East has distributed food in several devastated neighbourhoods in West Mosul. Shamil, Saabira and Ahmed, who have all received emergency relief, recount the time during and after Islamic State.By Kim Wiesener, Communication Manager, November 2017

When the front line reached Shamil’s street in West Mosul, about ten Islamic State warriors entered his house and set up camp there while awaiting the arrival of their enemy. They did not let any of the inhabitant’s escape, using them as human shields to avoid air strikes.

The following day, the war came to Shamil’s house. While the IS warriors on the second floor were shooting at the advancing Iraqi troops, he and his family had to seek refuge in a relatively safe place.

“They were fighting in my house. We were sitting underneath the staircase, and I was trying to protect my three daughters and my mother. One of the IS soldiers was shot, but I don’t know if he died,” Shamil says.

His house was badly damaged during the fighting. A few months later he and his 12-year old daughter, Rufaa, are sitting among a group of neighbours recounting their experiences during and after the regime of Islamic State – and especially the turbulent time when heavy fighting was going on in their neighbourhood.

We meet them at a safe address in West Mosul. It is still too risky for foreigners to be too visible in this part of the city, which until recently was still a battlefield.

Families adapted

On the way to the house, we drive through areas where war has left a very visible trace. Many houses are completely destroyed, car wrecks are everywhere, and the walls that still stand are full of shotholes. To enter West Mosul, you have to cross the Tigris River using a temporary floating bridge. The real bridges have been destroyed.

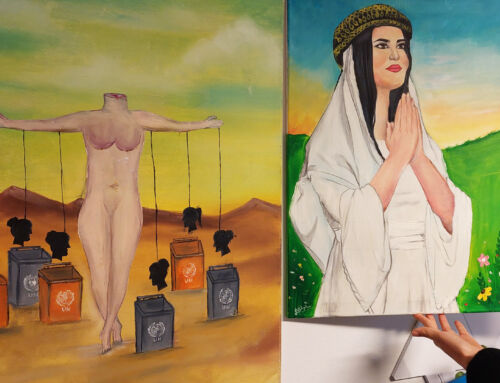

For almost three years, Iraq’s second-largest city was occupied by Islamic State – or Daesh, as it is called here. People had to adapt, otherwise the repercussions could be serious.

The men were punished

”I followed their rules to protect my family,” says Saabira, a well-educated mother of five, who lost her husband a few months ago. She is dressed in black, in mourning, and does not want to be photographed, but she readily recounts the ordeal that she and her neighbours have experienced.

“If a woman did not wear a veil, they did not harm her, but took her back to her house. If she was married, they took her husband, and if she was a young girl, they took her father or one of her brothers and punished them – either by throwing them into prison or take money from them. So the man was punished if the woman did not follow the rules,” Saabira says.

Off with the beard

One could also expect to be imprisoned or fined if one did not wear the particular trousers that Islamic State required. It was worse to be caught with a mobile phone. This could get you hanged, says Ahmed, a young clean-shaven man.

”I did not have a beard before Daesh, but they forced me to have one. Now I shaved it off again. They were looking for any pretext to imprison young men or punish them. You were not allowed to wear a ring, you were not allowed to smoke a cigarette,” he says.

So the population adapted, kept a low profile and waited for something to happen. None of the inhabitants of Mosul that we talked to believed that the IS regime would last. As Ahmed remarks: “No one wanted them, neither locally nor internationally, everyone was against them.”

Many dead

”We expected a war, we knew that it would come, everyone knew it,” Saabira says. She and her family started to hoard food. When the war came, it cost her husband his life. On a March morning, he left his house to meet his best friend from the neighbourhood. A shell struck just next to them, and they both died.

A few weeks later, Saabira that thought that it was her turn – and her kids’. An IS warrior attempted to turn his car into a suicide bomb. It was parked next to her house and would not start, but government forces were aware of it, and an air strike was pending.

“We were hiding in the room at the back, we were very frightened, we embraced each other and cried.” Her neighbours did not survive the war. A father and his four children were hit by a bomb. Many others lost their lives during the battle of Mosul.

Timely food supplies

Several months have passed since Saabira, Ahmed and Shamil’s neighbourhood was liberated. Times have been hard, water and electricity is lacking. Recently, they were placed on a list of beneficiaries when Mission East distributed food in West Mosul, and the supplies arrived just in time for Shamil and his family.

”When they were fighting in our house, our food supplies were destroyed. We are grateful for the help, we really needed it at the time,” he says.

Although West Mosul has been severely damaged by the fighting, it is slowly returning to life. A few shops have been reopened, there are more people on the streets, and in a few places there are even signs of reconstruction.

Back to school

For Shamil’s daughter, Rufaa, liberation has been particularly significant. For the first time in three years she is attending school. When Islamic State occupied Mosul in 2014, they sent the girls home from school. “I am so happy to be back at school. I have been sitting indoors for three years,” Rufaa says with a big smile that briefly conceals that she is visibly marked by the violent experiences she has been through.

Abdullah, a young man wearing shorts – possibly because of the intense heat, possibly as a delayed rebellion against Islamic State that banned such attire – tries to be optimistic: “We hope to return to a normal life. We hope that the displaced people will return, including the Christians and Yezidis. We hope that the children will go back to school. This really should happen,” he says.

Ahmed adds: “Daesh is gone, so the future looks brighter.”

For safety reasons, the names of the people interviewed for this article have been changed. Their real names are known to Mission East.