More than 600 children attend the Mission East child centre in a poor neighbourhood in the Iraqi city of Kirkuk. Most of them have been displaced by war. At the centre they can play, learn and process the often harrowing experiences they have been through.

By Kim Wiesener, Communication Manager, November 2017

With a delighted grin, Yusuf whacks the ball. He seems like a happy little boy when he runs around in the big classroom during a break, playing an improvised football game with the guests from Mission East. At night, things are different. When Yusuf is asleep, the nightmares come. He is afraid that his father will be shot.

Together with many other children, Yusuf attends the Mission East child centre in the impoverished neighbourhood of Wahed Hozairan in the Iraqi city of Kirkuk. Like them, he carries horrible memories of war, violence and escape.

This includes Ali, a quiet eight-year old boy, who spent some happy childhood years in a village just outside the city of Mosul. Then the extremist group, Islamic State, occupied the area, and the school that Ali had just started to attend was hit by a shell during the fighting.

Following that violent experience, Ali withdrew into himself. According to his grandmother, Inaya, who has accompanied him to the child centre, he showed signs of post-traumatic stress. “He constantly wanted to be with his mother or me. When she or I accompanied him to school, he refused to go into the classroom by himself,” she recalls.

Ali is flourishing

These days, Ali attends the child centre twice a week, and lately he has been flourishing. He boldly tells his adult relatives that he can easily walk to the centre by himself. “I like coming here. I used to be afraid, but I love being here, I feel safe,” Ali says.

When asked what he likes best about the child centre, the eight-year old answers without hesitation. The school subjects are in first place, and these include Arabic, English and math. Learning is an important part of the programme at the centre where children aged 6 to 14 years have the chance to play, learn and process the often harrowing experiences they have been through. They receive a form of psychological first-aid – or psycho-social support, as it is called.

The majority of children have been displaced from their homes. In Wahed Hozairan there are many families that have had to flee the conflict. For the 600 children who regularly attend the centre, the two weekly visits are a welcome break from an often tough and uncertain existence.

Violent memories

Sara, 22, is the centre supervisor. She meets many children with memories of violence. “The war often enters the classroom. I feel it when I talk to the children. It is part of the psychosocial support that they talk about their experiences. Sometimes they cry because they relive their experiences. A boy saw her father get shot, a girl saw a baby be murdered,” she says.

Sara listens to the children – and not only when she teaches them. “Even when I am sitting at my desk, they come over to me and talk. They feel safe, and I let them talk and show them my support. I try to remind them of the good things in life,” Sara says. “The children love to come here,” she adds. “When the mother of one of the girls wanted to take her daughter shopping to buy her a gift, the child said: ‘You go and buy things for money, I prefer to go to the child centre.’”

Afraid of weapons

Ghaida, 7, also loves the centre. Her family had to leave everything behind when escaping from Islamic State, and now they find it difficult to make ends meet in Kirkuk. But her mother, Ishaal, says that the children are happy when they attend the centre. “They look forward all day to coming here. I can see the changes in them,” she says.

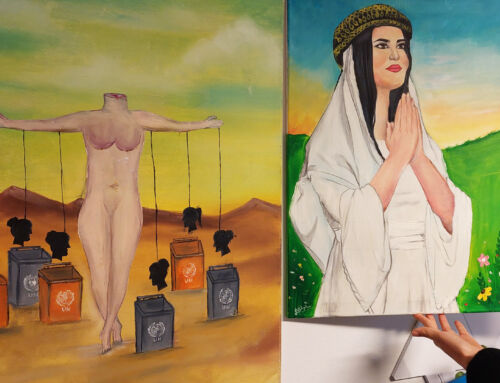

Ghaida enjoys the lessons. She likes drawing and excels at funny cartoon figures as well as beautiful, poetic birds. Men one thing she does not want to recall. “I don’t like weapons. I hate them,” she says, and her facial expression turns dark.

But Ghaida looks a lot happier when she is asked to perform a song. Soon, her bright voice fills up the room, and for a brief moment, it seems to erase the children’s unpleasant memories.

The names of those interviewed have been changed for safety reasons. Mission East knows their real names.