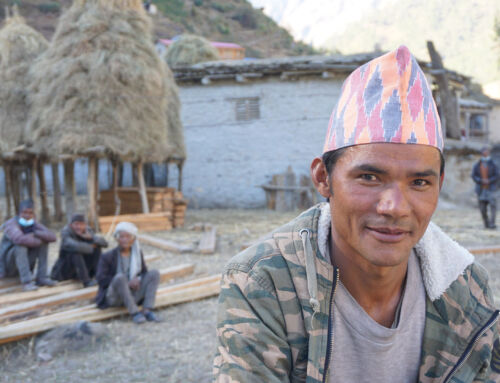

Unwanted and hidden, denied access to education and unable to go outside of the four walls of their home. For people with disabilities, there are many barriers to overcome, both physical, as well as barriers that exist in the minds of other people. In Tajikistan, children with disabilities are hidden away. In Armenia their parents are reproached for having given birth to them. And in Nepal, persons with disabilities are seen as useless in the harsh mountainous areas, where poverty is so great that there is rarely enough food for the whole family.

Mission East’s disability expert Vera van Ek has worked with disability rights in Nepal for several years, and she says: “In Nepal’s mountainous regions, I very rarely see children or adults with cerebral palsy. They simply do not survive the first years of life because the parents have given the larger part of the food to their healthy children instead.” Those who do manage to grow up despite severe disabilities, live a life at the fringe of society in an already indescribably poor area.

Disability is not about impairment

Disability is, according to the UN definition, not caused by any impairment in itself, but through the barriers people encounter in their daily life. “For example,” says Vera van Ek, “I need reading glasses, but it does not mean that I have a disability. For as long as I have my glasses, I function fine. But if I lived in a remote mountainous area where it is not possible to get glasses, my problem with vision becomes a disability.”

The poorest of the poor

When Mission East works with issues of disability in the countries of Armenia, Tajikistan and Nepal, the main focus is therefore, to eliminate and overcome barriers in the community. This applies both to physical barriers, such as lack of medical attention and difficulty in accessing buildings, institutional barriers, reflected in inappropriate legislation and lastly, attitudinal barriers which often results in persons with disabilities being regarded as worthless in many places.

Still, there is a difference in how the work is carried out in the three countries. In Armenia and Tajikistan, Mission East has established centres where children with disabilities are trained by qualified personnel and get professional medical help for rehabilitation. At the same time Mission East helps in creating organizations working for the rights of people with disabilities, including influencing legislators. In Nepal things must be dealt with differently.

“It is often not worthwhile making distinct disability projects out there, since people live in settlements that are widely scattered. It does not make sense to spend a lot of money on making a wheelchair ramp, if there is only one person with walking difficulties in the village and the rest of the population in general do not have enough food for the rest of the year,” explains Vera van Ek. But that does not mean that one should not focus on disability. “Persons with disabilities are the poorest of the poor. There is a clear and established link between disability and poverty. It is therefore a very important group to keep in mind when you want to reduce poverty in general, “she says.

Inclusion ensures participation

That is why Vera van Ek and Mission East’s Nepalese partner organisation Women Welfare Service (WWS) work by the principle that everyone should be included. By ensuring the involvement of persons with disabilities in all development projects, ranging from disaster response to literacy groups for women, they ensure that persons with disabilities are a part of society on an equal par with others, and allow them to get their views on decisions that concern them.

For example, disability and disaster management are closely connected in the mountains of Nepal. Firstly, fires, mudslides and falling from the steep mountainsides are frequent causes of disability. Secondly, persons with disabilities are the most vulnerable when disaster strikes because they are not able to reach a safe place as easily as the other villagers. For this reason it is important to involve people with disabilities when working with disaster management. This can, for example, influence our choice of location when planning meetings. “If we hold a meeting on disaster risk reduction, we make sure to place it in a room with enough light for the visually impaired, allowing them to view and participate in the meetings,” explains Vera van Ek.

In order to do away with the prejudices that people with disabilities encounter, Vera van Ek has developed a number of games where the other villagers are made aware of how vulnerable people with disabilities are. For example, people are blindfolded, so they can see what it’s like to be blind. “Once they are made aware of how it is, they have an incredible understanding of how difficult the situation is for persons with disabilities,” she says.

A person with disabilities is not a disabled person

In Mission East’s projects and communication, we never refer so someone as a ‘disabled person’. Instead the term ‘person with disabilities’ is used. This is to stress that persons with disabilities are people on equal footing with others, and that the disability is not the defining feature of one’s whole identity. This terminology is used by all disability organizations, the UN and the World Health Organization.

Gender and disability

In developing countries there is a clear correlation between disability, gender and marginalization. Women and girls with disabilities encounter double as much discrimination because they are both women and have a disability. Mission East helps the local Nepalese organisation Women Welfare Service (WWS) in including women with disabilities in their projects.