The security situation in Afghanistan is the worst since the Taliban war started. Public infrastructure has collapsed, and even die-hard war correspondents are increasingly staying away. But how do ordinary Afghans handle the permanent state of emergency? The Afghans have an ability to find solutions where there are none, Mission East’s experience shows.

“We sit here drinking tea and playing games. It’s just a way to kill time because we’re scared and powerless about what’s happening in our country.”

That’s what Simi Jan, TV2’s Freelance Correspondent in Afghanistan, is saying on the radio programme “People and Media” of the Danish National Broadcast about how her Afghan girlfriends in Kabul keep their fear at bay. Afghanistan is still one of the poorest countries in the world. And the war, which is soon entering its 20th year, is intensifying. It is getting bloodier year by year.

Afghan people are survivors

Sometimes it is difficult to understand how ordinary Afghans, surrounded by fighting actions, hunger and the absence of all kinds of infrastructure, can make an everyday life work without surrendering in total despair. So what are the resources that Afghans are drawing on to survive both physically and mentally?

In order to gain insight into this, we have talked to former East Mission Country Manager in Afghanistan, Benny Werge.

“Afghans are extremely resilient. People don’t fall asleep, ” Benny recalls.

“It was something I really noticed during my time out there. People come to work, no matter what, if they have to drag themselves with a broken leg. No none stays at home just because they do not feel like going to work one day, like here in Denmark, where we have a very high work force absence due to “illness”. ”

It is because there is a very strong survival instinct among Afghans, Benny says, which is manifested by the fact that many bury themselves in duties and work:

“No matter how bad it is, you cannot just sit back”.

Stronger solidarity, more selfishness

The downside to this survival instinct, however, is that the way people treat each other sometimes gets tough:

“Afghans are not always sweet to each other. Even within the same village, it is not unusual for them to fight each other, because they are fighting for the same resources. ” But other times, it is precisely this resource scarcity that creates an extraordinarily strong relationship within the family and the village, Benny says:

“If you are hungry you can always meet up with a family member and be served. It’s not something you just do here in Denmark. Afghans also send money to family members who are unable to flee. ”

Thus, the war has, paradoxically, fostered solidarity on the one hand and sharpened selfishness on the other. And when it comes to solidarity, it’s interesting to note how women have responded to the absence of the state, Benny points out:

“The women have built their own security system in the absence of the state. Savings associations for women within the village, which often do not work elsewhere in the world, work because there is a high degree of social control and one is concerned with protecting the honor of the family. So no one is stealing. ”

Believing in herself

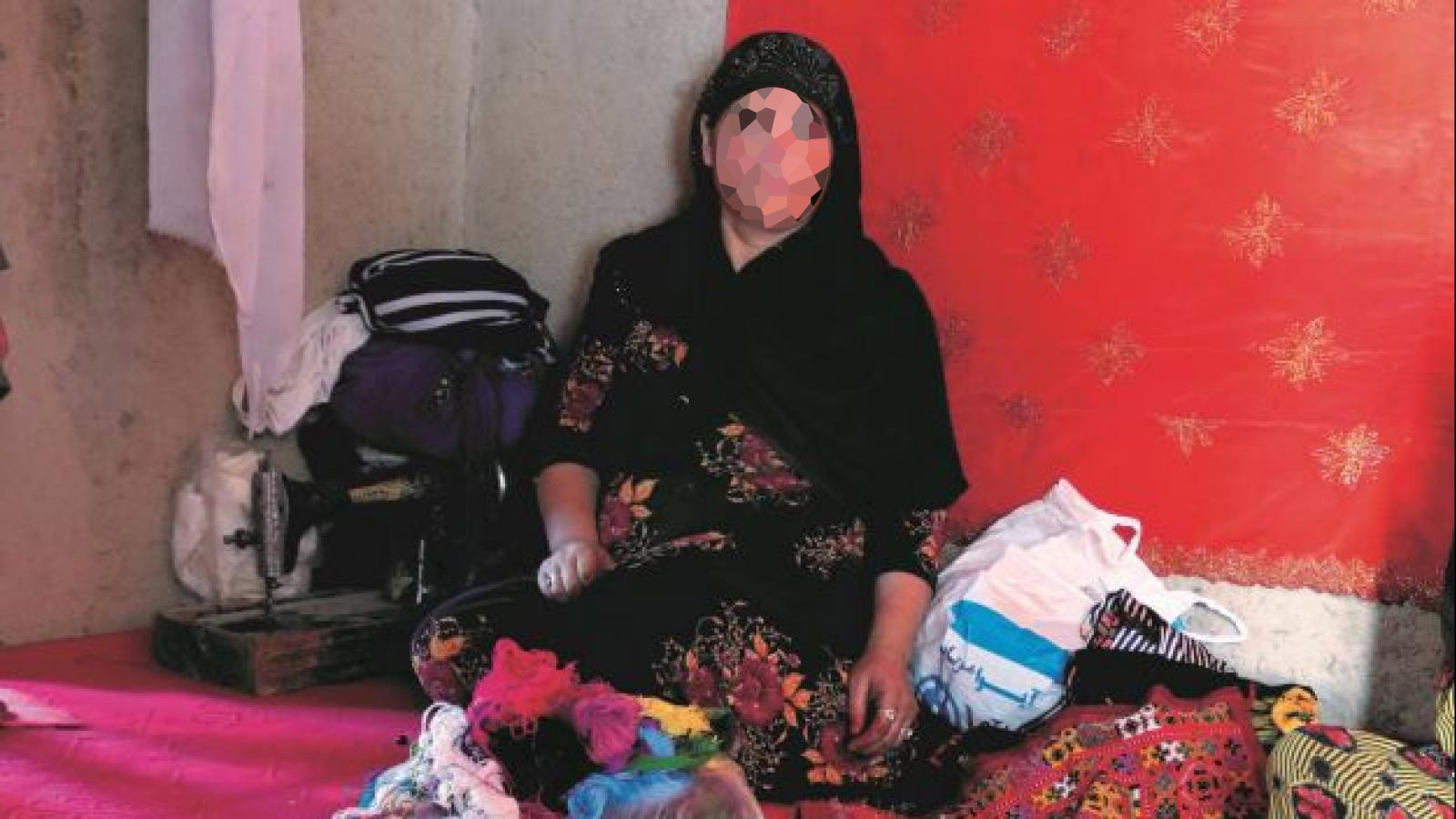

Saleha is excatly one of those Afghan women who finds solutions where there are none, unless she does something herself. She is a woman of 49 from Takhar province. Her husband was hit by mental disability 14 years ago so he could no longer support the family of nine people. Saleha’s eldest son has also lost the ability to contribute to family livelihood since he was injured in a fight against the Taliban.